AI, Automation, and Power: Revisiting Old Fears in the Age of Big Tech

Automation anxiety hits knowledge workers

Artificial Intelligence (AI) stands today at the heart of global conversations about the future of work. News headlines often cast AI as either the spark for a new economic golden age or the catalyst of a displacement crisis, where machines handle tasks once reserved for human cognition. Yet, seen against a broader historical backdrop, today’s “automation anxiety” has a familiar shape. The mid-twentieth century witnessed comparable debates over mechanization, computers, and processes collectively termed “automation.” In shifting from factory floors to digital domains, these concerns have shed light on how society adapts (or fails to adapt) to radical technological change. In this essay I examine the origins of the automation question, its evolution during the rise of the knowledge economy, and its echoes in current AI controversies. Along the way, I highlight the roles of government panels, corporate influence, and—crucially—Big Tech’s efforts, at times, to evade or dilute regulatory oversight.

1. Early Debates on Automation

On a crisp evening in 1963, the faint glow of a Midwestern steel mill illuminated the once-bustling town of Gary, Indiana. For two decades, this plant had symbolized the American industrial machine: forging steel beams for skyscrapers, employing generations of workers, and paying wages that supported entire families. Yet, inside that cavernous space, newly installed mechanical arms now welded metal at speeds unimaginable just five years earlier. Workers watched these robot-like systems with a mix of fascination and dread, whispering among themselves about whether this spelled the end of secure employment.

This vivid scene was hardly unique. Mechanization—often described under the umbrella of “automation”—was sweeping manufacturing sectors nationwide. Alarmed by the implications for workers, President Kennedy’s Panel on Automation and Technological Progress (1962) held hearings to assess whether mass unemployment might soon ensue (Commission on Automation, 1962). Their focus: How rapidly could the economy realistically absorb displaced employees, and who bore responsibility for retraining people whose jobs disappeared?

Into this flurry of debate dropped the “Triple Revolution” Statement (1964), penned by influential social critics who coined the term “cybernation” to describe computer-driven processes capable of replacing whole categories of labor (Triple Revolution Statement, 1964). Critics warned that laissez-faire acceptance of automation might replicate the economic pattern foretold by John Maynard Keynes’s (1930) concept of “technological unemployment”—where machines’ efficiency leaves human workers behind.

Against this backdrop, opinions diverged. Labor union reps and progressive economists predicted permanent havoc, fearing that after agriculture and manufacturing, automation would creep into service roles as computers improved. Their alarm was that future expansions in productivity might not require a commensurate expansion in the labor force, begetting swaths of jobless communities like Gary, Ind.

On the other hand, a more optimistic cadre pointed to history’s track record. Throughout the Industrial Revolution, new technologies destroyed some jobs but created others—often higher skilled and better paid. Daniel Bell’s The End of Ideology (1960) portrayed technology as a force demanding new social and economic institutions, not necessarily promising disaster. Meanwhile, Norbert Wiener’s writings on cybernetics (1948) foreshadowed a world of self-regulating machinery, urging caution about technology’s disruptive capacity, yet also hinting at potentially enormous benefits in productivity.

For communities like Gary, the 1960s question was visceral: Would our bright mechanized future lighten drudgery and poverty, or hollow out the blue-collar backbone of the nation? In many ways, the same tension resonates today whenever we weigh the pros and cons of AI.

2. The Lull in Automation Debates & The Rise of the Information Society

As the 1970s gave way to the 1980s, talk of large-scale displacement receded. Instead, the computers that once threatened to eliminate jobs became viewed as valuable tools—particularly in administrative, financial, and technical fields. By the 1990s, the conversation hinged increasingly on a “post-industrial” or “information society” motif, where data and services dislodged heavy industry as prime economic drivers.

New York City’s financial district offers a vivid historical microcosm. In the late 1970s, haggard clerks, mired in piles of paper-based transactions, dreaded the arrival of computational machines that could handle trades faster and more reliably than human hands. Yet by 1985, the same firms were expanding, hiring software specialists, “quants,” and technical analysts, many of whom owed their roles to the very technologies that replaced manual processes.

Daniel Bell’s The Coming of Post-Industrial Society (1973) laid the intellectual foundation for calling these white-collar, knowledge-intensive roles the new pillars of economic growth. Concurrently, Marc Uri Porat’s The Information Economy (1977) for the U.S. Department of Commerce decreed that information was not merely an adjunct but rather a central raw material of modern production, like iron ore for steel. Over time, personal computers proliferated across offices. Rather than throngs of workers marching to city factories, the 1980s and 1990s saw rising demand for project managers, network administrators, and other knowledge professionals.

Adding another layer, sociologist Manuel Castells’s The Rise of the Network Society (1996) emphasized that new communication technologies do not simply automate tasks; they reshape how societies organize production, markets, and even personal relationships. In Castells’s formulation, a “networked” mode of economic activity emerges, where digital connectivity supersedes geography. Instead of being just a factory cog, workers increasingly became nodes in vast webs of global collaboration—meeting virtually, sharing data, and delivering services across time zones.

Within this network society, the fear of sudden mass job destruction lessened (compared to the 1960s) because new internet-based industries—ranging from e-commerce to IT consulting—seemed to be fueling job creation. Meanwhile, anecdotal victories in technology-driven productivity overshadowed the older doomsday scripts. The “automation debate” wasn’t dead, but it felt overshadowed by talk of “upskilling” and “lifelong learning.” Governments and private firms alike promoted digital literacy, positing that a decent education plus computer skills equaled job security in the brave new economy.

Several factors muted the automation controversy during these decades. In addition to the upsurge in white-collar STEM roles, the heyday of globalization meant manufacturing outsourcing often overshadowed purely technological displacement. As factories shifted to lower-wage countries, domestic policy discussion pivoted to trade, competitiveness, and workforce retraining, rather than fixating on machines forcibly replacing humans at home.

Yet the lull masked developing tensions. While computers in the office were arguably less threatening than factory robots, fresh forms of inequality loomed. Beginning in the mid-2000s, a handful of tech-centric corporations began accruing unprecedented clout, building global supply chains, capturing consumer data, and capitalizing on intangible assets. Even as many in government lauded technology’s capacity to “lift all boats,” concerns simmered that powerful players in Big Tech already sought to mold regulation—or avoid it altogether—to secure billions in profits from newly networked economies.

3. The New Era of Automation Anxiety

The emergence of AI has resurrected automation anxiety, spotlighting that disruptive technology is nothing new—but it may be accelerating and broadening. Where industrial robots once replaced assembly-line workers, today’s AI algorithms analyze financial portfolios, review legal documents, write software code, and even produce creative works.

One reason AI looms so large is that it goes beyond performing physical or highly rule-based tasks. It intrudes into realms like language interpretation, high-level decision-making, and creative ideation. When investment banks start using AI-driven analytics to replace entire teams of junior associates, old assumptions about “safe” cognitive work unravel. Some praise this shift as freeing employees for more strategic, imaginative tasks. Others worry that even software engineers or attorneys could lose ground to an ever-advancing wave of machine intelligence.

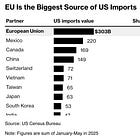

In data from the McKinsey Global Institute (2017), up to 375 million workers globally may need to switch occupational categories by 2030 to accommodate automation—an enormous upheaval dwarfing even the 1960s predictions of assembly-line displacement. Various studies highlight that the shape of these transitions depends on the pace of AI adoption, sectoral differences, and the adaptability of educational structures and social policies.

Frey and Osborne (2013) famously forecast that nearly 47% of U.S. jobs were at risk of computerization. Though their methodology and conclusions sparked debate, the alarm helped catalyze policy conversations internationally. The McKinsey Global Institute’s (2019) follow-up reports caution that while not every job will vanish outright, substantial portions of many professions are likely to be automated. Even if comprehensive job replacement is less prevalent than alarmists predict, partial automation can impose severe pressures on workers, forcing rapid retraining and upending career trajectories.

Meanwhile, the OECD (2018) found that while 14% of existing jobs in member countries could be fully automated, a larger share—32%—face major task alterations. Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo (2020) further note that new technologies often substitute “routine” tasks, but they can complement more advanced or creative ones. In essence, AI’s net impact will hinge on occupation-specific variables, policy environments, and market demand for new skill sets.

At the heart of all these studies lies a question that haunted Gary’s steel workers six decades ago: How will we adapt to a technology that can perform a core component of our work more cheaply, efficiently, or reliably? The difference is that while mechanical automation targeted physical tasks, AI targets cognitive, creative, and communicative roles. Societies are revisiting perennial dilemmas about:

Skill Obsolescence: If half of a worker’s tasks can be automated, does that worker remain as a half-skilled employee or must they “reskill” entirely? The speed of AI development intensifies worries that skill sets could become outdated within a few years.

Economic Inequality: In a Castells-style network society, control over data, computing resources, and distribution channels can yield vast wealth for those at the helm. Large technology firms—already among the most capitalized institutions worldwide—might capture the lion’s share of AI-driven productivity gains, exacerbating existing income and wealth gaps. OpenAI's Sam Altman speaks of the coming "one-person billion dollar companies."

Policy & Governance: Past decades saw government panels and commissions grappling with how to shape automation’s effects. Now, there is renewed impetus for universal basic income (UBI), job guarantees, or frameworks for AI safety net programs. Still, critics warn that Big Tech’s outsized influence—through lobbying, strategic philanthropy, or public-relations narratives—can stall or soften regulation designed to ensure societal benefit. Such policies have currently undergone serious setbacks in the United States, but that does not mean that other countries are not serious about AI regulation.

Recent scholarship from the Knight First Amendment Institute, “AI as Normal Technology,” posits that AI might be less a revolutionary break than an incremental addition to our longstanding technological evolution. The authors argue institutions relate to AI through existing legal and political mechanisms, provided we maintain vigilance about emergent inequalities and develop flexible regulatory structures.

However, historical precedents suggest a pattern: the larger and more profitable technology corporations become, the greater their capacity to shape the rules. During the industrial era, certain conglomerates funneled resources into regulatory capture, ensuring policies favored them or remained lax. Today, the so-called “Big Tech” sector invests heavily in lobbying across major economies. Critics allege that these corporations co-opt ethical AI forums, sponsor studies and conferences, and even help draft legislation to maintain minimal oversight. While these same firms tout ambition to “democratize AI,” skeptics argue that—much like the large industrial trusts of the 19th century—today’s tech giants often evade regulation that might limit their data monopolies, hamper micro-targeted advertising, or require transparent AI auditing. Hence, bridging “AI as Normal Technology” with the realpolitik of corporate power demands a healthy vigilance to avoid complacency and ensure that historical cycles of unbalanced power and under-regulation do not repeat themselves.

Conclusion

Whether in a 1960s steel mill or a 2020s AI-driven startup, technology’s influence on work remains fraught with both fears of obsolescence and the promise of progress. The uncertain interplay of job losses and job gains mirrors longstanding tensions from the days of President Kennedy’s Commission on Automation to the knowledge-economy optimism of the 1980s and ’90s. Manuel Castells broadened our understanding by highlighting how networks—rather than mere physical machinery—structure economic life. Today, AI extends that logic, suggesting that even tasks believed to be uniquely human may be automated, or at least fundamentally reshaped.

Yet, this story is as much about power and governance as it is about technology itself. From the earliest labor union protests against robot arms to present-day controversies over AI regulation, politics and policy define how societies channel technological shifts. Big Tech, flush with capital and data, can either use its heft to foster equitable innovation or to fortify monopolies that entrench inequality. Historical precedent warns that relying on self-regulation and goodwill alone can be naïve. Robust frameworks, whether in the form of antitrust action, stringent auditing, or new AI governance structures, have proven critical to guiding innovation in ways that serve the many, rather than the few.

Ultimately, the crux of today’s automation debate remains the same as it was decades ago: How do we harness technological potential without sacrificing livelihoods and social welfare? The answer lies in directing AI’s trajectory through deliberate policy, enforcing corporate accountability, and an engaged public. As technology continues to evolve—be it in an automated car plant or a deep-learning lab—remembering Gary’s steel mill can remind us that progress is not merely about new machines, but about new ways to ensure that innovation benefits all.

References

Acemoglu, D. & Restrepo, P. (2020). Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets. Journal of Political Economy, 128(6), 2188–2244. Link to Publisher’s Version: University of Chicago Press

Bell, D. (1960). The End of Ideology: On the Exhaustion of Political Ideas in the Fifties. Glencoe, IL: Free Press. WorldCat Library Record

Bell, D. (1973). The Coming of Post-Industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting. New York: Basic Books. WorldCat Library Record

Castells, M. (1996). The Rise of the Network Society. Oxford: Blackwell. WorldCat Library Record

Commission on Automation. (1962). An Interim Report of the President’s Panel on Automation and Technological Progress. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Full Text via HathiTrust

Drucker, P. (1969). The Age of Discontinuity: Guidelines to Our Changing Society. New York: Harper & Row. Full PDF via Internet Archive | Google Books Entry

Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. A. (2017). The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation? Oxford Martin Programme on the Impacts of Future Technology, University of Oxford. Original Working Paper PDF

Keynes, J. M. (1930). Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren. In Essays in Persuasion (1963 ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. Full Text at Marxists.org

Knight First Amendment Institute. (n.d.). AI as Normal Technology. Direct link

McKinsey Global Institute. (2017). A Future that Works: Automation, Employment, and Productivity. Full Report PDF

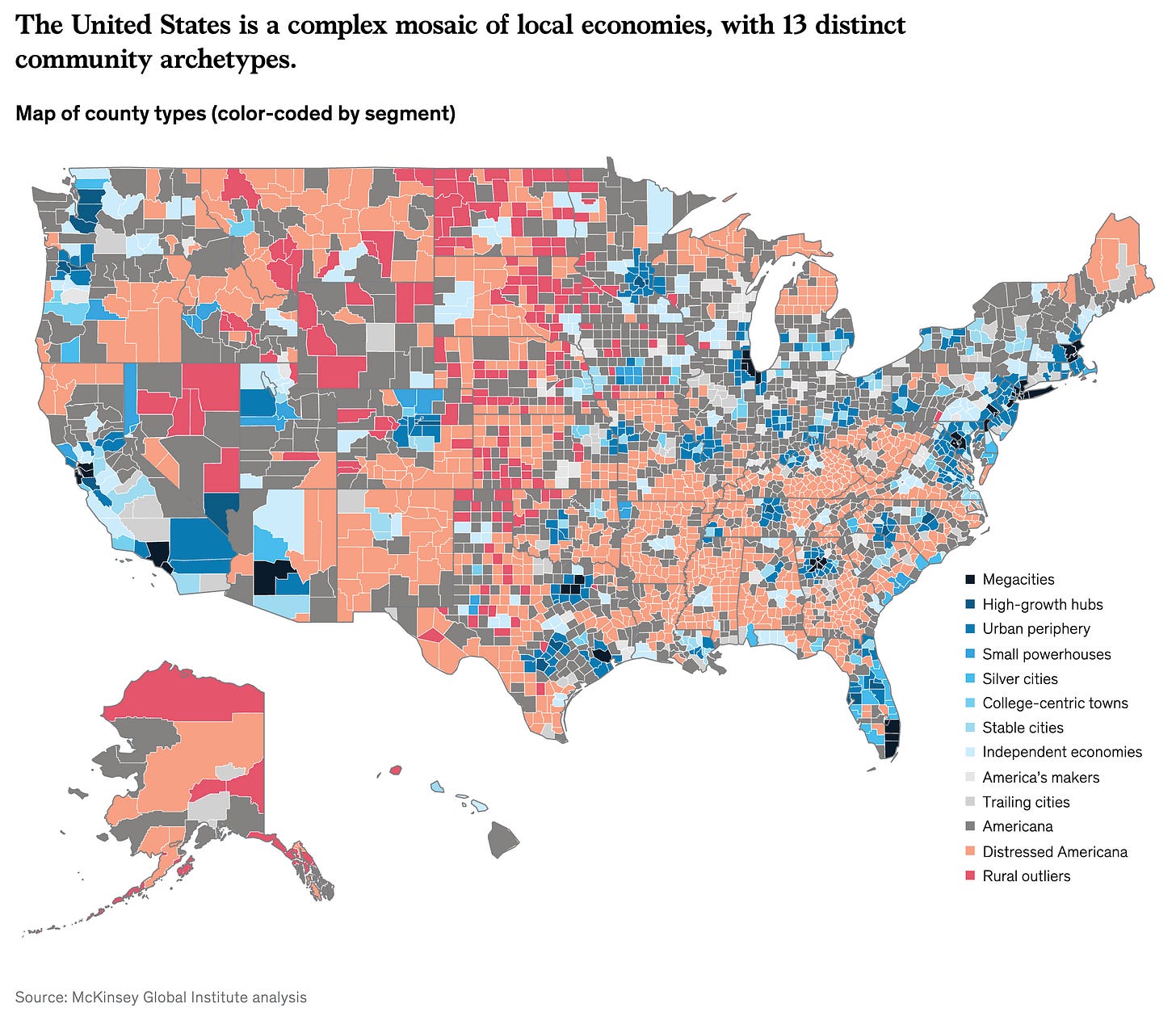

McKinsey Global Institute. (2019). The Future of Work in America: People and Places, Today and Tomorrow. Full Report PDF

Norbert Wiener. (1948). Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Internet Archive Full Text

OECD. (2018). Automation, Skills Use and Training. Paris: OECD Publishing. OECD iLibrary Link

Porat, M. U. (1977). The Information Economy (Volumes 1–9). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce. Open Library Link

Triple Revolution Statement. (1964). The Triple Revolution: Cybernation, Weaponry, & Human Rights. National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy. Full Statement PDF via Internet Archive

I really enjoyed reading this article. It is a very balanced approach to the issue.